Kernels and Kernel Regression

The kernel trick allows us to move from regression over a predefined set of basis functions to regression in infinite spaces. All of this is predicated on understanding what a kernel even is and how to construct it. In this post, we will see exactly how to do this and how to use kernels for regression.

← Evidence Function Extras in kernel regression →

Hopefully, by this point you are extremely comfortable with the linear regression problem and it’s Bayesian interpretation. Starting with this post, we are going to explore what happens when, and how we can use, more parameters than data points. This is enabled by the kernel trick.

When we introduced linear regression, we allowed the usage of the basis functions $h\left(\cdot\right)$ which mapped the inputs of our problem to features in a different space, allowing us to learn non-linear functions over the input space. This greatly improves the expressiveness of the linear regression model, but is still quite limited as we can only use a finite (and usually small) number of hand-crafted basis functions. We will now look into using more basis functions than data points, and specifically how introducing kernels enables much greater flexibility in the functions the linear regression model can learn.

More Parameters than Data Points

In the classical setting of linear regression, it is typical to hear that “the number of parameters has to be smaller than the number of data points”. However, in the Bayesian framework the number of parameters or data points doesn’t matter all that much. Consider the MMSE function based on some prior $\theta\sim\mathcal{N}\left(\mu_{\theta},\Sigma_{\theta}\right)$:

\[\begin{align} f_{\hat{\theta}}\left(x\right) & =h^{T}\left(x\right)\hat{\theta}\\ & =h^{T}\left(x\right)\left(\frac{1}{\sigma^{2}}H^{T}H+\Sigma_{\theta}^{-1}\right)^{-1}\left(\Sigma_{\theta}^{-1}\mu_{\theta}+\frac{1}{\sigma^{2}}H^{T}y\right) \end{align}\]As long as $\Sigma_{\theta}$ is PD, then $\hat{\theta}_{\text{MMSE}}$ always exists. If there aren’t many data points, then the model falls back on the prior for predictions. If there are many data points, then the prior is mostly ignored for predictions. So, in general, the function $h\left(\cdot\right)$ can be as expressive as we want.

However, if $h\left(\cdot\right)$ maps to very high dimensions, then we have a different, mostly computational problem. Say $h:\mathbb{R}^{d}\rightarrow\mathbb{R}^{p}$ and $p$ is about a million, then it is infeasible to invert the matrix $H^{T}H+\Sigma_{\theta}^{-1}$ - it will be a huge matrix! To take this to the absurd, if $h\left(\cdot\right)$ is a function that maps to an infinite number of basis functions, what then? It would be helpful if there was a way for us to get past these mostly computational costs.

Return of the Equivalent Form

Recall that we saw two forms for the MMSE estimate $\hat{\theta}$ that were equivalent. Suppose for a moment that we have a very simple prior $\theta\sim\mathcal{N}\left(0,I\lambda\right)$. Then

Notice that here the matrix we have to invert is dependent on the number of data points, not number of parameters. In fact, the matrix $HH^{T}$ is composed only of inner products of the basis functions between points:

\[\begin{equation} HH^{T}=\left[\begin{matrix}h^{T}\left(x_{1}\right)h\left(x_{1}\right) & \cdots & h^{T}\left(x_{1}\right)h\left(x_{N}\right)\\ \vdots\\ h^{T}\left(x_{N}\right)h\left(x_{1}\right) & \cdots & h^{T}\left(x_{N}\right)h\left(x_{N}\right) \end{matrix}\right] \end{equation}\]Let’s try to take advantage of this fact.

Dual Problem

If we put the definition of the equivalent form instead of the standard form into the MMSE function, we get:

\[\begin{equation} f_{\hat{\theta}}\left(x\right)=h^{T}\left(x\right)H^{T}\left(HH^{T}+I\frac{\sigma^{2}}{\lambda}\right)^{-1}y \end{equation}\]Suddenly, everything here is written in terms of the inner products of the basis functions, instead of the outer product, after all:

\[\begin{equation} h^{T}\left(x\right)H^{T}=\left[\begin{matrix}h^{T}\left(x\right)h\left(x_{1}\right)\\ \vdots\\ h^{T}\left(x\right)h\left(x_{N}\right) \end{matrix}\right] \end{equation}\]where $x$ is a newly observed point and $x_{1},\cdots,x_{N}$ are our training examples.

Let’s define:

\[\begin{equation} K=HH^{T}\quad;\quad k\left(x\right)=Hh\left(x\right) \end{equation}\]and rewrite the MMSE function one more time (we’re getting there, I promise):

\[\begin{align} f_{\hat{\theta}}\left(x\right) & =k^{T}\left(x\right)\overbrace{\left(K+I\frac{\sigma^{2}}{\lambda}\right)^{-1}y}^{\stackrel{\Delta}{=}\alpha}\\ & \stackrel{\Delta}{=}k^{T}\left(x\right)\hat{\alpha}=f_{\hat{\alpha}}\left(x\right) \end{align}\]This looks a lot like the regular linear regression! Only now, instead of $p$ basis functions with $h:\mathbb{R}^{d}\rightarrow\mathbb{R}^{p}$, we have $N$ basis functions with $k:\mathbb{R}^{d}\rightarrow\mathbb{R}^{N}$. This linear regression problem is called the dual problem to the primal problem that depends on $\theta$.

The Trick

So far, we only really manipulated the math into a form which depends on inner products. As is, it seems like a kind of useless exercise in math, since we still always have to calculate the vectors $h\left(x\right)$ anyway. But it turns out we can bypass this evaluation.

Suppose that instead of defining the basis functions $h\left(\cdot\right)$ we directly calculate the inner products. That is, instead of defining $h\left(\cdot\right)$, we will define the following function:

\[\begin{equation} k\left(x_{i},x_{j}\right)=h^{T}\left(x_{i}\right)h\left(x_{j}\right) \end{equation}\]If such a function $k\left(\cdot,\cdot\right)$ exists, then we won’t ever have to actually calculate the (possibly very large) vectors $h\left(x_{i}\right)$ and will only have to calculate a number for each inner product. If $N\ll p$, this silly trick can cut out a lot of needless computations.

This trick is called the kernel trick and the dual form of the solution that we saw above (with $\hat{\alpha}$) is called kernel regression.

Positive Semi-Definite Kernels

Let’s start by actually defining a kernel.

Definition: Positive Semi-Definite (PSD) Kernels A symmetric function $k:X\times X\rightarrow\mathbb{R}$ is called a PSD kernel on the set $X$ if the associated kernel matrix (also known as the Gram matrix) $K_{ij}=k\left(x_{i},x_{j}\right)$ is PSD for any set of distinct points $\left{ x_{i}\right} _{i=1}^{N}\subseteq X$

This definition alone already gives us some information on the type of functions that are valid kernels:

Claim: As a by-product, if we have any two functions $g:\mathbb{R}^{m}\times\mathbb{R}^{m}\rightarrow\mathbb{R}$ and $h:\mathbb{R}^{m}\rightarrow\mathbb{R}^{n}$ such that: $g\left(x_{1},x_{2}\right)=h\left(x_{1}\right)^{T}h\left(x_{2}\right)$ then $g\left(\cdot,\cdot\right)$ is a PSD kernel (which we will just call a kernel for now).

Proof:

Let’s define:

\[\begin{equation} H^{T}=\left[\begin{matrix}-h\left(x_{1}\right)^{T}-\\ -h\left(x_{2}\right)^{T}-\\ \vdots\\ -h\left(x_{n}\right)^{T}- \end{matrix}\right]\in\mathbb{R}^{m\times N} \end{equation}\]where we have $N$ points $x_{1},x_{2},\ldots,x_{N}$. The Gram matrix is defined as:

\[\begin{equation} G=H^{T}H\Rightarrow G_{ij}=h\left(x_{i}\right)^{T}h\left(x_{j}\right) \end{equation}\]As we have seen before, any the product of a matrix with it’s transpose is a PSD matrix, which means that $G$ is PSD, which in turn means that $g\left(\cdot,\cdot\right)$ is a kernel. So, for any symmetric function $k\left(\cdot,\cdot\right)$, if we can show that it is the inner product of two vectors, then the function is a kernel. $\square$

Now the connection to basis functions should be easy to see - any set of basis functions defines a kernel.

Examples

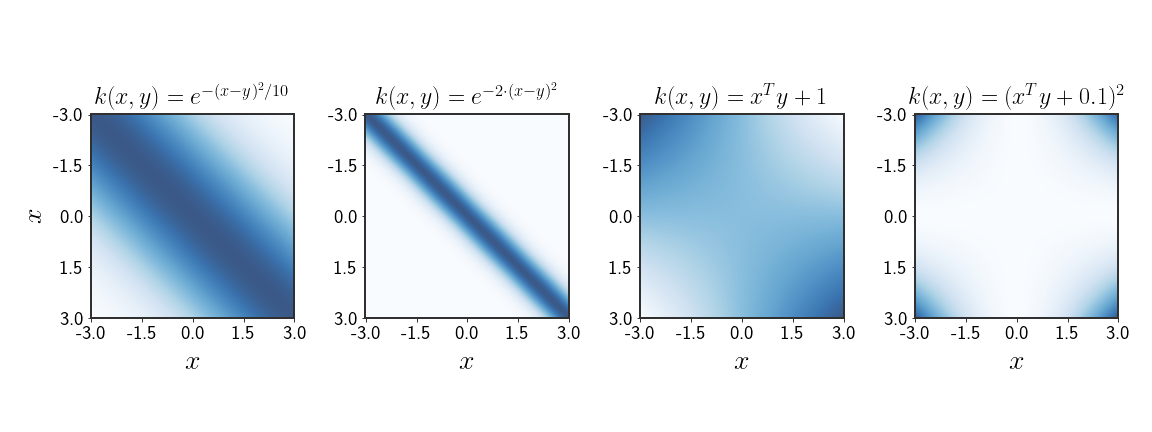

Let’s go over some examples for valid and non-valid kernels. Hopefully this will build a good intuition of whether something is a PSD kernel or not.

-

$k\left(x,y\right)=c$ where $c>0$ is some constant This is quite obviously a valid kernel, since the Gram matrix will be made fully of $c$ s and we have:

\[\begin{align*} a^{T}Ka & =a^{T}\left(c\boldsymbol{1}\right)\boldsymbol{1}^{T}a\\ & =\sum_{i}a_{i}c\cdot\sum_{i}a_{i}\\ & =c\sum_{i}a_{i}\sum_{i}a_{i}\\ & =c\left(\sum_{i}a_{i}\right)^{2}\ge0 \end{align*}\] -

$k\left(x,y\right)=f\left(x\right)^{T}g\left(y\right)$ where $f\left(\cdot\right)\neq g\left(\cdot\right)$ One of the basic definitions of a PSD kernel is that it is symmetric. However, for this function:

\(k\left(x,y\right)=f\left(x\right)^{T}g\left(y\right)\neq f\left(y\right)^{T}g\left(x\right)=k\left(y,x\right)\) so $k\left(\cdot,\cdot\right)$ is not a valid kernel

-

$k\left(x,y\right)=\text{cov}[x,y]$ When we build the Gram matrix using this function for any finite set of points, we actually build a covariance matrix, which we have shown is a PSD matrix. So this is a valid kernel

-

$k\left(x,y\right)=-x^{T}y$ Recall that for a PSD matrix $A$ and any vector $v$ , the following must hold: \(v^{T}Av\ge0\) Now, if we choose the unit vector $e_{i}$ as $v$ , we have: \(e_{i}^{T}Ae_{i}=A_{ii}\) where $e_{i}=\left(0,\ldots,0,\overbrace{1}^{i\text{th index}},0,\ldots,0\right)$ . From this we directly see that for any $i$ , $A_{ii}\ge0$ must hold in order for $A$ to be PSD. In kernels this is equivalent to showing that $k\left(x,x\right)\ge0$ . In the case of this vector, $k\left(x,x\right)<0$ is a very real possibility, so there is no way that the Gram matrix will be PSD, so it is not a valid kernel

Okay, okay, that’s enough examples. From the above there are two rules we can clearly see:

- If there exists two vectors $x$ and $y$ such that $k\left(x,y\right)\neq k\left(y,x\right)$ then $k\left(\cdot,\cdot\right)$ is not a valid kernel

- If there exists a vector $x$ such that $k\left(x,x\right)<0$ then $k\left(\cdot,\cdot\right)$ is not a valid kernel

However, there are some functions that do not violate these two rules but are still not kernels, so we need to be especially careful with how we define our functions and whether they are actually valid kernels or not.

Constructing Kernels

We’ve shown that we can think of any set of basis functions as one part of a kernel, but if we always do this then we fall back to the problem of having to pick the set basis functions, instead of choosing the kernel directly. We have also shown that it is kind of a pain to prove if something is a valid kernel or not, in the general case. We will now go on to show how kernels can be constructed directly

Since a kernel is valid as long as the Gram matrix on any set of points is PSD, we can create building blocks, and stack them on top of each other to get more complex kernels. For any two valid kernels $k_{1}\left(\cdot,\cdot\right)$ and $k_{2}\left(\cdot,\cdot\right)$ the following functions will also be kernels:

- $c\cdot k_{1}\left(x,y\right)$ where $c>0$ is a constant

- $f\left(x\right)k_{1}\left(x,y\right)f\left(y\right)$ where $f:\mathbb{R}^{n}\rightarrow\mathbb{R}$

- $q\left(k_{1}\left(x,y\right)\right)$ where $q\left(\cdot\right)$ is any polynomial with non-negative coefficients

- $\exp\left(k_{1}\left(x,y\right)\right)$

- $k_{1}\left(x,y\right)+k_{2}\left(x,y\right)$

- $k_{1}\left(x,y\right)k_{2}\left(x,y\right)$

- $k\left(x,y\right)=x^{T}Ay$ where $A$ is PSD

Using these building blocks, we can create more and more complex kernels, as we see fit.

Example: Polynomial Kernel

Using the construction blocks, we saw that a polynomial of a kernel with non-negative coefficients is, itself, a valid kernel. Let’s look at the specific case:

\[\begin{equation} k\left(x,y\right)=\left(x^{T}y\right)^{2} \end{equation}\]where $x,y\in\mathbb{R}^{2}$ . This is clearly a kernel because claims (3) and (7) are used to construct it. However, we want to understand exactly why this is a valid kernel. This becomes quite clear when we take a closer look at the function:

\[\begin{align*} \left(x^{T}y\right)^{2} & =\left(x_{1}y_{1}+x_{2}y_{2}\right)^{2}\\ & =x_{1}^{2}y_{1}^{2}+2x_{1}y_{1}x_{2}y_{2}+x_{2}^{2}y_{2}^{2}\\ & =\left(\begin{matrix}x_{1}^{2} & \sqrt{2}x_{1}x_{2} & x_{2}^{2}\end{matrix}\right)\left(\begin{matrix}y_{1}^{2}\\ \sqrt{2}y_{1}y_{2}\\ y_{2}^{2} \end{matrix}\right)\\ & =p_{2}\left(x\right)^{T}p_{2}\left(y\right) \end{align*}\]So, the kernel is actually the inner product between two basis functions, which in this case happen to be second order polynomials. The function $p_{2}\left(\cdot\right)$ maps a vector $x$ to all possible 2nd order terms, times some constants:

\(\left(\begin{matrix}x_{1}^{2} & \sqrt{2}x_{1}x_{2} & x_{2}^{2}\end{matrix}\right)^{T}\) In the same manner, if we would have chosen a kernel of the form $\left(x^{T}y\right)^{m}$ , then it would map from the features into all possible $m$ -th order terms of the features.

Now, instead, let’s look at the following:

\[\begin{align*} \left(x^{T}y+1\right)^{2} & =\left(x_{1}y_{1}+x_{2}y_{2}+1\right)^{2}\\ & =x_{1}^{2}y_{1}^{2}+x_{2}^{2}y_{2}^{2}+1+2x_{1}y_{1}+2x_{2}y_{2}+2x_{1}y_{1}x_{2}y_{2} \end{align*}\]And we’re not going to even bother writing this in vector form. Notice that now the expression holds all terms up to the 2nd degree. This would also be true for any degree $m$ where $\left(x^{T}y+1\right)^{m}$ would expand all features up to (and including) the $m$ -th degree. It is also really easy to see that this is still a valid kernel, using the claims from earlier. The kernel:

\[\begin{equation} k_{m}\left(x,y\right)=\left(x^{T}y+1\right)^{m} \end{equation}\]is called the polynomial kernel exactly because of the characteristics we described.

RBF is a Valid Kernel

A family of basis functions that are often used in practice are the radial basis functions (RBF). The most common function from this family is the Gaussian basis function:

\[\begin{equation} h_{\mu}\left(x\right)=\exp\left[-\frac{\left(x-\mu\right)^{2}}{2s^{2}}\right] \end{equation}\]which we have already talked about. However, instead of defining the function’s center ( $\mu$ ), we can define a kernel based on this basis function, that uses the distance between any two points:

\[\begin{equation} k\left(x,y\right)=\exp\left[-\frac{1}{2}\left(x-y\right)^{T}A\left(x-y\right)\right] \end{equation}\]where we have broadened our definition by adding $A$ as any PSD matrix. This kernel is very widely used in literature and in practice.

Claim: The Gaussian kernel is a valid kernel

Proof:

For the proof we will use several of the claims for constructing kernels. We begin (as usual) by expanding the Mahalanobis distance:

\[\begin{equation} \left(x-y\right)^{T}A\left(x-y\right)=x^{T}Ax-2x^{T}Ay+y^{T}Ay \end{equation}\]We can now rewrite the function as:

\[\begin{align} k\left(x,y\right) & =\exp\left[-\frac{1}{2}x^{T}Ax\right]\exp\left[x^{T}Ay\right]\exp\left[-\frac{1}{2}y^{T}Ay\right]\\ &\stackrel{\Delta}{=}f\left(x\right)\exp\left[\underbrace{x^{T}Ay}_{q\left(x,y\right)}\right]f\left(y\right) \end{align}\]Notice how we brought the form of the whole function as the form in claim (2) (i.e., multiplied by a function on either side). Since $A$ is a PSD matrix, $q\left(x,y\right)$ must also be a valid kernel. Using claim (4), the exponent of a kernel is also a kernel, therefore $k\left(\cdot,\cdot\right)$ is a valid kernel. $\square$

The Gaussian kernel can actually be rewritten as:

where $k_{n}\left(\cdot,\cdot\right)$ is the $n$ -th order polynomial kernel. Remember how we opened up the polynomial kernel into the inner product between two vectors? For this kernel, we would have to build infinitely long vectors, with every polynomial degree in it, and then find the inner product of these two vectors. In this sense, we can think of the kernel as a basis function $h\left(\cdot\right)$ that maps inputs into infinite feature spaces.

Frequentist Derivation of Kernel Regression

We saw how we can manipulate the Bayesian linear regression to the form of kernel regression. But the same can be done in the frequentist framework, starting from ridge regression

First, remember that the loss function for ridge regression is given by:

\[\begin{equation} L\left(\theta\right)=\|H\theta-y\|^{2}+\lambda\|\theta\|^{2} \end{equation}\]Deriving this by $\theta$ and equating to 0 we see that:

\[\begin{align} 2\frac{\partial}{\partial\theta}L\left(\theta\right) & =-H^{T}H\theta+H^{T}y+\lambda\theta\stackrel{!}{=}0\\ \Rightarrow\theta & =\frac{1}{\lambda}H^{T}\left(H\theta-y\right) \end{align}\]We can now define:

\[\begin{align} \theta & =\frac{1}{\lambda}H^{T}\left(H\theta-y\right)=\frac{1}{\lambda}\sum_{i}\overbrace{\left(h\left(x_{i}\right)^{T}\theta-y_{i}\right)}^{\alpha_{i}}h\left(x_{i}\right)\\ & \stackrel{\Delta}{=}\sum_{i}\alpha_{i}h\left(x_{i}\right)\stackrel{\Delta}{=} H^{T}\alpha \end{align}\]So we can rewrite the solution for $\theta$ as a linear function of the functions that make up $H$, where $\alpha_{i}$ is the coefficient for the basis functions over the $i$-th sample $h\left(x_{i}\right)$.

The minimum of $L\left(\cdot\right)$ with respect to $\alpha$ is:

\[\begin{align*} L\left(\alpha\right) & =\|HH^{T}\alpha-y\|^{2}+\lambda\|H^{T}\alpha\|^{2}\\ \Rightarrow\frac{\partial}{\partial\alpha}L\left(\alpha\right) & =HH^{T}HH^{T}\alpha-HH^{T}y+\lambda HH^{T}\alpha\stackrel{!}{=}0 \end{align*}\]If we assume that $HH^{T}$ is invertible, we get:

\[\begin{equation} \hat{\alpha}_{ML}=\left(HH^{T}+I\lambda\right)^{-1}y \end{equation}\]which is very similar to the solution we saw for ridge regression with $\theta$. Now, let’s plug this into the linear regression function:

\[\begin{align} f\left(x\right) & =\hat{\theta}_{ML}^{T}h\left(x\right)=\hat{\alpha}_{ML}^{T}Hh\left(x\right)\\ & =y^{T}\left(HH^{T}+I\lambda\right)^{-1}Hh\left(x\right) \end{align}\]Defining the Gram matrix $K=HH^{T}$ such that $K_{ij}=h\left(x_{i}\right)^{T}h\left(x_{j}\right)$ and the vector $k\left(x\right)$ where $k_{i}\left(x\right)=h\left(x\right)^{T}h\left(x_{i}\right)$, then we can rewrite the above as:

\[\begin{equation} f\left(x\right)=y^{T}\left(K+I\lambda\right)^{-1}k\left(x\right) \end{equation}\]Suppose that, instead of defining the basis functions $h\left(\cdot\right)$, we define a kernel $k\left(x_{i},x_{j}\right)$. While before it was not so obvious how this would fit into the structure of the linear regression, now all we need to define is $K_{ij}=k\left(x_{i},x_{j}\right)$ and $k_{i}\left(x\right)=k\left(x,x_{i}\right)$ in order to get the prediction for a new point $x$.

Now the reason we allow PSD and not only PD kernels might be easier to see. Since the matrix we are inverting is $\left(K+I\lambda\right)$, even if the Gram matrix $K$ is not PD (i.e. not invertible) and only PSD, because of the added term $I\lambda$, the whole matrix is PD. Under this reasoning, and because forming PSD kernels is easier than forming PD kernels, we can relax our restrictions on the form of the kernels and use PSD kernels, giving us just a bit more freedom.

Discussion

The kernel trick allows us to move from a small number of parameters, to many more parameters than data points even. While classically using more (meaningful) parameters than data points makes no sense, in the Bayesian framework of linear regression, there is no reason not to use many parameters. Because we added a prior of the values of the parameters, the complexity of the results is efficiently mitigated.

However, it is still not exactly clear how to use kernels, or what priors over kernels really mean. Moreover, moving from basis functions to kernels actually introduces some difficulties. In the next post we will look into all of these aspects of kernel regression.