Gaussian Processes

Going one step further into kernel regression, Gaussian processes allow us to define distributions (i.e. priors) over the predictive functions themselves.

← Extras in kernel regressionDiscriminative classification →

In the previous posts we considered kernels and how they can be used in the context of Bayesian linear regression or ridge regression. In this post, we will consider a more mathematically rigorous investigation into how the kernels effectively define a distribution over functions.

Priors Over Functions

Once we moved to regression in the domain of kernels, defining a prior on the parameters makes no sense. In the first place, there might be an infinite number of parameters. Moreover, the regression is defined over the learned functions, not a set of parameters. Finally, it’s simply hard to understand what the effects of the prior will be in the space of parameters, since there’s so many of them.

Instead, we will attempt to move from distributions over parameters to a distribution over functions, more rigorously influencing our choices instead of simply saying “we can exchange basis functions with kernels”.

Distributions On Functions

Having defined this goal, we immediately have a problem (of course). What does it mean to define a density on a function? A function is like taking random vectors to the extreme. Instead of having a finite set of elements in the vector, we have a continuum of elements. There is no way to define a distribution with full support on such a space directly.

But we still might want to prioritize certain types of functions over others. For instance, we could sat that “smooth functions” are more likely than “jagged functions”, in some sense. Such definitions of which functions are more or less likely directly correspond to the behavior of neighboring inputs and outputs. That is, saying a function is usually smooth means that for an input $x$ and its’ neighbor $x+\epsilon$, the outputs should be quite similar, i.e. $f(x)\approx f(x+\epsilon)$. This is a concrete criterion for which functions we are more likely to see.

So instead of trying to define a distribution over the space of functions, we will try to say how their outputs are related to each other.

Stochastic Processes

A stochastic process is the realization of the properties mentioned above. Instead of defining a probability directly on the function, $p(f)$, stochastic processes explain how we should expect a finite set of outputs to be jointly distributed.

So, for a finite set of points $x_1,\cdots,x_N$, a stochastic process instead compares the joint distribution:

\[\begin{equation} p(f(x_1),\cdots,f(x_N)) \end{equation}\]If this is define for any finite set of points, then we implicitly have a distribution over functions. After all, we typically think of functions as a mathematical object which receives an input and returns an output.

In this post, we will consider a specific example of this concept.

Gaussian Processes

Definition: Gaussian Process

A Gaussian Process (GP) is a, possibly infinite, collection of random variables, any finite number of which have a joint Gaussian distribution

Equivalently, we will say that $f$ is a Gaussian process:

\[\begin{equation} f\left(x\right)\sim\mathcal{GP}\left(m\left(x\right),k\left(x,x'\right)\right) \end{equation}\]with some mean function $m:\mathbb{R}^{d}\rightarrow\mathbb{R}$ and covariance kernel function $k:\mathbb{R}^{d}\times\mathbb{R}^{d}\rightarrow\mathbb{R}$ if for any finite set of points $x_1,\cdots,x_N$ the outputs $f=\left(f\left(x_{1}\right),\cdots,f\left(x_{N}\right)\right)^{T}$ have a Gaussian distribution given by:

\[\begin{equation} f\sim\mathcal{N}\left(\mu,C\right) \end{equation}\]where $C_{ij}=k\left(x_{i},x_{j}\right)$ and $\mu_{i}=m\left(x_{i}\right)$.

Bayesian linear regression as a GP

A very simple example of a GP is Bayesian linear regression $f\left(x\right)=h\left(x\right)^{T}\theta$ with $\theta\sim\mathcal{N}\left(0,\Sigma_\theta\right)$. The mean of $f$ with respect to $\theta$ is given by:

\[\begin{equation} \mathbb{E}\left[f\left(x\right)\right]=\mathbb{E}\left[h^{T}\left(x\right)\theta\right]=h^{T}\left(x\right)\mathbb{E}\left[\theta\right]=0 \end{equation}\]and the covariance:

\[\begin{equation} \text{cov}\left[f\left(x\right)\right]=h^{T}\left(x\right)\text{cov}[\theta]h\left(x\right)=h^{T}\left(x\right)\Sigma_{\theta}h\left(x\right) \end{equation}\]So if the prior $\theta$ is Gaussian, then $f\left(\cdot\right)$ is also a Gaussian distribution for any finite set of points, which is exactly the definition of a GP. The GP defined by Bayesian linear regression with a Gaussian prior is:

\[\begin{equation} f\left(x\right)\sim\mathcal{GP}\left(0,h^{T}\left(x\right)C_{\theta}h\left(x'\right)\right) \end{equation}\]Regression with GPs

Predictions with Exact Observations

Before moving on to the more general task of predicting new values when we know that our training has some added sample noise, let’s look at the noiseless version. Suppose that we have, as our training set, the pairs $\{ x_{i},f(x_{i})\}_{i=1}^{N}\stackrel{\Delta}{=}\{ x_{i},f_{i}\}_{i=1}^{N}$ and we get a new point $x_{*}$. We want to predict the value of $f\left(x_{*}\right)\stackrel{\Delta}{=} f_{*}$ given the training set $\left{ x_{i},f_{i}\right}_{i=1}^{N}$.

Notice that, directly from the definition of a Gaussian process, we know that the finite set of points $f_{1},f_{2},\ldots,f_{N},f_{*}$ are jointly a Gaussian distribution given by:

\[\begin{equation} \left[\begin{array}{c} f\\ f_{*} \end{array}\right]\vert\left\{ x_{i}\right\} ,x_{*}\sim\mathcal{N}\left(0,\left[\begin{array}{cc} K & k_{*}\\ k_{*}^{T} & \quad k\left(x_{*},x_{*}\right) \end{array}\right]\right) \end{equation}\]where $k_{*}\stackrel{\Delta}{=}\left(k\left(x_{1},x_{*}\right),k\left(x_{2},x_{*}\right),\ldots,k\left(x_{N},x_{*}\right)\right)^{T}$. Let’s define $\kappa\stackrel{\Delta}{=} k\left(x_{*},x_{*}\right)$ and from now on we will stop conditioning on the observed $x$s. $f_{*}\vert f$ is simply the conditional of a Gaussian distribution, something we’ve already seen multiple times:

\[\begin{equation} f_{*}\vert f\sim\mathcal{N}\left({k_{*}^{T}K^{-1}f,\ \ \;\kappa-k_{*}^{T}K^{-1}k_{*}}\right) \end{equation}\]Note that $K$ must be PD for any finite set of points $X$ in order for the above solution to exist. Since $K$ is the Gram matrix of $k\left(\cdot,\cdot\right)$ on the points $X$, then we are restricted to only using PD kernels in the noise-free version of the GP regression. Finding PD kernels may be extremely non-trivial, however the Gaussian kernel we’ve seen and talked about before \emph{is} PD.

Predictions with Sample Noise

In the real world, we rarely have noise-free observations. Instead, what we observe is actually:

\[\begin{equation} y_{i}=f\left(x_{i}\right)+\eta_{i} \end{equation}\]where $\eta_{i}\sim\mathcal{N}\left(0,\ \sigma^{2}\right)$ and $f$ is a GP. In this case, the covariance of 2 samples $y_{i}$ and $y_{j}$ will be:

\[\begin{align} \text{cov}\left[y_{i},y_{j}\right] & =\text{cov}\left[f\left(x_{i}\right)+\eta_{i},f\left(x_{j}\right)+\eta_{j}\right]=k\left(x_{i},x_{j}\right)+\sigma^{2}\cdot\mathbb{I}\left[i=j\right]\\ & \stackrel{\Delta}{=} k\left(x_{i},x_{j}\right)+\sigma^{2}\delta_{ij} \end{align}\]where $\delta_{ij}=1$ if $i=j$ and 0 otherwise. The full covariance matrix of the vector $y=\left(y_{1},y_{2},\ldots,y_{N}\right)^{T}$ is then given by:

\[\begin{equation} \text{cov}\left[y\right]=K+\sigma^{2}I \end{equation}\]The joint probability of $y$ with the new point $f_{*}$ is now:

\[\begin{equation} \left[\begin{array}{c} y\\ f_{*} \end{array}\right]\sim\mathcal{N}\left(0,\left[\begin{array}{cc} K+\sigma^{2}I & k_{*}\\ k_{*}^{T} & \quad k\left(x_{*},x_{*}\right) \end{array}\right]\right) \end{equation}\]Notice that we didn’t add the sample noise to $k\left(x_{*},x_{*}\right)$ - this is because we want to predict the true underlying value, without adding noise to our prediction. Once again, this is a Gaussian distribution, so we already know how to find the conditional distribution of $f_{*}$:

\[\begin{equation} f_{*}\vert y\sim\mathcal{N}\left(k_{*}^{T}\left(K+\sigma^{2}I\right)^{-1}y,\ \ \;\kappa-k_{*}^{T}\left(K+\sigma^{2}I\right)^{-1}k_{*}\right) \end{equation}\]Since the above is Gaussian, the MMSE and MAP solutions are:

\[\begin{equation} f_{MMSE}\left(x_{*}\right)=y^{T}\left(K+\sigma^{2}I\right)^{-1}k_{*} \end{equation}\]Multiple Inputs

Suppose we want to predict the responses to $m$ new data points, not just 1. In this case, the conditional distribution will be a multivariate Gaussian. If the new points are $Z=\{z_{i}\}_{i=1}^{m}$, then we want to calculate the probability $f_Z\vert y$ where $f_{Z}=\left(f\left(z_{1}\right),f\left(z_{2}\right),\ldots,f\left(z_{m}\right)\right)^{T}$. The joint probability is, once again, Gaussian:

\[\begin{equation} \left[\begin{array}{c} y\\ f_{Z} \end{array}\right]\sim\mathcal{N}\left(0,\left[\begin{array}{cc} K+\sigma^{2}I & C\\ C^{T} & \quad K_{Z} \end{array}\right]\right) \end{equation}\]where $C\in\mathbb{R}^{N\times m}$ is a matrix with the indexes $C_{ij}=k\left(x_{i},z_{j}\right)$ and the matrix $K_{Z}\in\mathbb{R}^{m\times m}$ is the Gram matrix for the samples in $Z$. The conditional distribution will be:

\[\begin{equation} f_{Z}|y\sim\mathcal{N}\left(C^{T}\left(K+\sigma^{2}I\right)^{-1}y,\ \ \;K_{Z}-C^{T}\left(K+\sigma^{2}I\right)^{-1}C\right) \end{equation}\]Notice that for multiple outputs, all of the outputs are dependent on each other as well! This is a consequence of our definition of GPs, but still, it’s something to remember. The MMSE/MAP is then given by:

\[\begin{equation} f_{Z}=C^{T}\alpha \end{equation}\]with the same $\alpha$ as before.

Sample noise as part of the kernel

Notice that the noisy version is equivalent to the noise-free version, only we use the kernel:

\[\begin{equation} \tilde{k}\left(x,y\right)=k\left(x,y\right)+\sigma^{2}\delta\left(y-x\right) \end{equation}\]instead of $k\left(\cdot,\cdot\right)$. In this variation, as long as we assume that there is some sample noise, we are free to use PSD kernels for $k\left(\cdot,\cdot\right)$, since $\tilde{k}\left(\cdot,\cdot\right)$ will always be PD.

The easiest way to see this is by using the definition of PD matrices directly:

\[\begin{align*} \forall v\quad v^{T}\left(K+I\sigma^{2}\right)v & =\underbrace{v^{T}Kv}_{\ge0}+\sigma^{2}\|v\|^{2}>0 \end{align*}\]So, if $K$ is PSD, then for any $\sigma^{2}>0$, the matrix $K+I\sigma^{2}$ is PD. In other words, if $K$ is the Gram matrix of $k\left(\cdot,\cdot\right)$, then $C+I\sigma^{2}$ will be the Gram matrix of $\tilde{k}\left(\cdot,\cdot\right)$, which will be PD.

Evidence

The evidence function allowed us to compare between Bayesian linear regression models, which allowed us to choose the model that best explains the training data. We would like to do the same for GPs. We are essentially looking for the marginal $y\vert\varphi$:

\[\begin{equation} y=f_{\varphi}+\eta \end{equation}\]where $\varphi$ are the hyperparameters of the kernel that defines the GP, $\eta\sim\mathcal{N}\left(0,\ I\sigma^{2}\right)$ and $f_{\varphi}=\left(f_{\varphi}\left(x_{1}\right),\ldots,f_{\varphi}\left(x_{N}\right)\right)^{T}$. First, we know that this marginal is Gaussian since the joint distribution of $y$ and $f_{\varphi}$ is Gaussian. Since we know that $y\vert\varphi$ is Gaussian, all we need to do is find the expectation and covariance, which will define the Gaussian:

\[\begin{equation} \mathbb{E}\left[y\right]=\mathbb{E}\left[f_{\varphi}\right]+\mathbb{E}\left[\eta\right]=0 \end{equation}\] \[\begin{align} \text{cov}\left[y\right] & =\text{cov}\left[f_{\varphi}+\eta\right]\nonumber \\ & =K_{\varphi}+I\sigma^{2} \end{align}\]So we see that:

\[\begin{equation} y\vert\varphi\sim\mathcal{N}\left( 0,\ K_{\varphi}+I\sigma^{2}\right) \end{equation}\]Explicitly, the log-evidence is given by:

\[\begin{align} \log p\left(y\vert\varphi\right) & =-\frac{1}{2}y^{T}\left(K_{\varphi}+I\sigma^{2}\right)^{-1}y-\frac{1}{2}\log\left|K_{\varphi}+I\sigma^{2}\right|-\frac{N}{2}\log\left(2\pi\right)\\ & =-\frac{1}{2}\underbrace{y^{T}\alpha_{\varphi}}_{\text{term 1}}-\frac{1}{2}\log\underbrace{\left|K_{\varphi}+I\sigma^{2}\right|}_{\text{term 2}}-\text{const} \end{align}\]The two terms in the log-evidence define a tradeoff between fitness (term 1) and simplicity (term 2):

- We can think of the matrix $\left(K_{\varphi}+I\sigma^{2}\right)^{-1}$ as a “projection matrix” onto the space defined by the kernel. When projecting $y$ onto this space, we get the vector $\alpha_{\varphi}$. If the inner product $y^{T}\alpha_{\varphi}$ is small, then the two vectors are considered very close in the space defined by the projection matrix $\left(K_{\varphi}+I\sigma^{2}\right)^{-1}$ - that is, the data is well explained by the model. So, a small distance under the metric defined by the kernel matrix is preferred over larger distances, equivalent to the training points already being well explained by the model

- The determinant $\vert K_{\varphi}+I\sigma^{2}\vert$ is equivalent to the volume in function space that is modeled by the GP. If $\vert K_{\varphi}+I\sigma^{2}\vert$ is large, then the GP “contains a lot of functions”. If it’s small, then it “explain few functions”. So, if we have two GPs and we have to choose between them, we would prefer the model that contains less functions

The above tradeoff is (somewhat) intuitive: we want a GP that describes as few functions as possible, such that our data is still explained by the GP.

Extra - Mean Function

In all we did above, we completely ignored the mean function $m\left(\cdot\right)$, and instead assumed that it is defined as $m\left(x\right)=0$. However, any mean function can be used in practice.

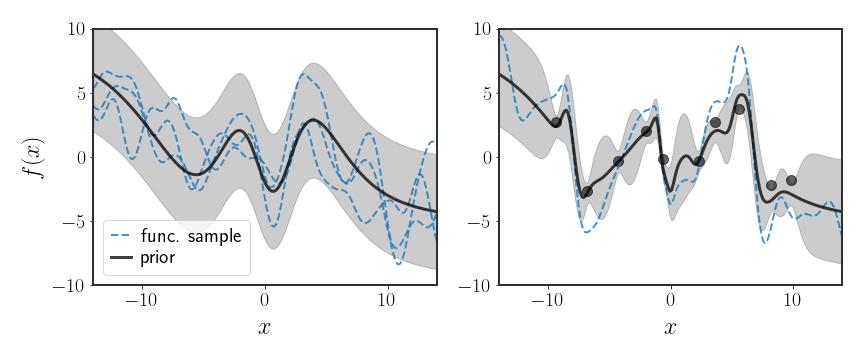

The above figure shows an example where the mean function is defined by some complicated neural network, $m\left(x\right)=\text{NN}_{\psi}\left(x\right)$ where $\psi$ are the parameters of the network. The GP is then defined as:

\[\begin{equation} f\sim\mathcal{GP}\left(\text{NN}_{\psi}\left(\cdot\right),\;k\left(\cdot,\cdot\right)\right) \end{equation}\]where $k\left(\cdot,\cdot\right)$ is some kernel of our choosing. Defining the GP in this way, we can think of the neural network as describing the overall behavior while the GP is added on top to fit the residuals, the data not well fit by the network. In fact, if we have the dataset $\mathcal{D}=\left{ \left(x_{i},f\left(x_{i}\right)\right)\right} _{i=1}^{N}$, then we can simply define:

\[\begin{equation} y\left(x\right)=f\left(x\right)-\text{NN}_{\psi}\left(x\right) \end{equation}\]and then $y$ can just be modeled as a zero-mean GP:

\[\begin{equation} y\sim\mathcal{GP}\left(0,\;k\left(\cdot,\cdot\right)\right) \end{equation}\]Of course, the choice of a neural function as the mean function is arbitrary. We could have chosen any functional form, and the above would be perfectly acceptable. So, if you have some reason to assume that $m\left(\cdot\right)$ has a specific form, then you can think of the added GP as a model for the deviations from the behavior described by $m\left(\cdot\right)$.

Discussion

On the surface, GPs aren’t that different from the kernel regression we saw in earlier posts. Conceptually, however, there was a bit shift. GPs implicitly define a distribution over functions directly, whilst in kernel regression we always assumed there were some set of parameters behind the scenes. This ties in nicely with the goal of regression. Many times we don’t really care about the parameters, but about the predicting function. GPs do this directly.

Many of the posts so far have been to do with regression with a Gaussian. The stage is now set to leave this setting. In the next few posts we will talk about classification. After that, we will return to the world of regression but with more complex priors, which significantly alters the behavior of the solutions and which problems we can solve.

← Extras in kernel regressionDiscriminative classification →