A Simplified Overview of Langevin Dynamics

An overview of Langevin dynamics (or sampling), with a focus on building up intuition for how it works, when it works, and what can be done to make it work when it doesn't.

Langevin dynamics (or sampling)

Problem Setting

Suppose we have the following distribution:

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:prob} p(x)\propto e^{-f(x)}\Leftrightarrow \log p(x)=-f(x)+\text{const} \end{equation}\]where $x\in\mathbb{R}^d$ and $f(x)$ is some function so that the integral $\intop e^{-f(x)}dx$ doesn’t diverge (i.e. $p(x)$ is a valid distribution).

We would like to sample from this distribution, but don’t have any way to do so directly. Worse, we don’t know the conditional or marginal distributions under this PDF, so we can’t use methods such as Gibbs sampling. However, what we do know is the gradient of the function at every point: $\nabla f(x)$

While we don’t know the distribution itself, we obviously know quite a bit about the distribution if we know how to differentiate it. Specifically, we can use gradient descent (GD) in order to find the modes of the distribution:

\[\begin{equation} x_t=x_{t-1} - \eta_t \nabla f(x_{t-1}) \end{equation}\]where $\eta_t > 0$ is a scalar usually called the learning rate or step size. If we can find the modes of the distribution, then it follows that we can find the areas with peaks in the density, i.e. areas which may be quite likely in the distribution. So while we may not know the distribution itself (only an unnormalized function that defines the distribution), the gradients actually tell us quite a bit about the function.

Langevin sampling, which will be introduced in the next section, looks like a weird modification of GD. We will see that it amounts to adding noise every iteration of the GD algorithm. An easy (but not entirely correct) way to start thinking about Langevin sampling is that if we add some kind of noise to each step of the GD procedure, then most of the time the chain will converge to areas around the biggest peaks, instead of arriving at a local maxima of the distribution.

Langevin Sampling

As I mentioned, the sampling algorithm is surprisingly simple to implement and is iteratively defined as:

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:langevin} x_{t+1}=x_t - \frac{\epsilon}{2}\nabla f(x_t)+\sqrt{\epsilon}\mathcal{N}\left(0,I\right) \end{equation}\]where $\epsilon>0$ is a (small) constant.

Let’s look at a simple example of this in action:

As you can see, the little dot (which follows $x_t$ though the iterations) moves around in the bright areas of the distribution. Sometimes it explores outside of the bright regions, only to return. In general, the whole distribution is explored pretty quickly , as we would want it to be.

Convergence

Using the update rule of equation \eqref{eq:langevin}, the sample $x_T$ will converge to a sample from the distribution

Usually each function we want to sample from requires different handling. Notice how in figure 1 it seems like ~200 steps are enough to reach a sample from the distribution. Now, let’s look at a slightly slower example:

The chain arrives at the distribution fast enough, but then stays in the upper half of the distribution for it’s whole life time - for 800 iterations! This means that if we want to sample two points , which are initialized close to each other, then they will probably be very close to each other even after 800 iterations. In MCMC terms, we would say that the chain hasn’t mixed yet. This is in contrast to the example in figure 1, where ~200 iterations are enough for the chain to mix.

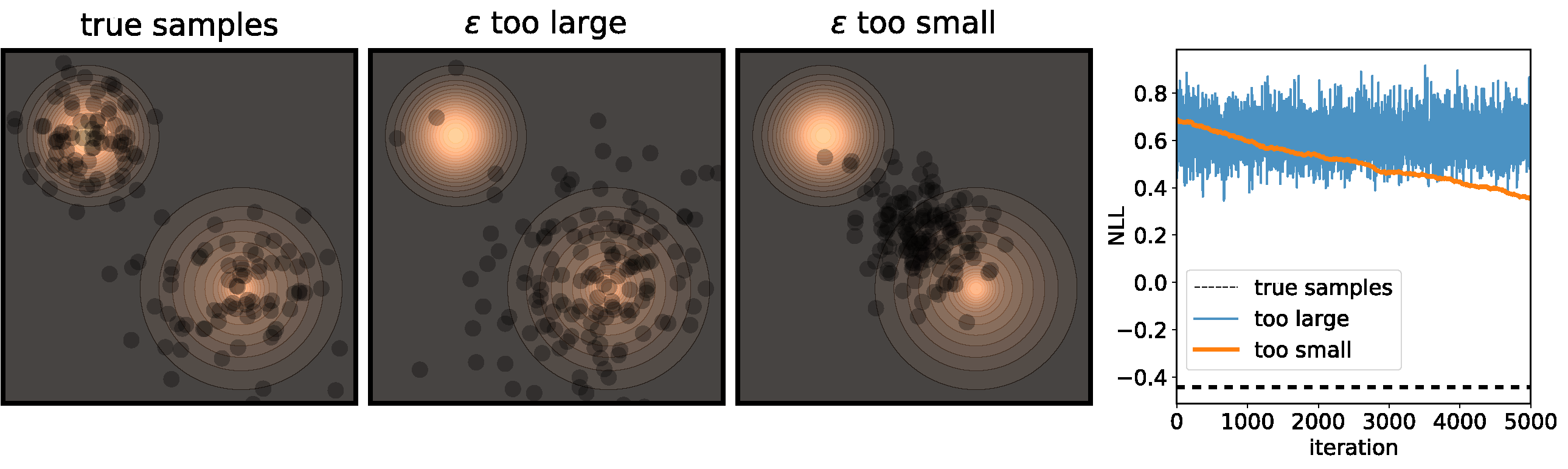

In this case, intuition calls for a very simple modification - change the step size! If we increase the step size, then the dot would move further each iteration, and the chain would “mix” very rapidly, right? However, finding the right value for $\epsilon$ is actually pretty difficult. Consider the following toy example:

Figure 3 illustrates the problems that can happen if $\epsilon$ isn’t correctly calibrated. If it is too large, then we’re adding a bunch of noise each iteration, so while the chain will converge at its’ stationary distribution very quickly, the stationary distribution will be very different from the distribution we actually want to sample from. On the other end of the spectrum, if $\epsilon$ is too small then it will take a very long time for the samples to move from their initial positions.

Okay, so forget about getting there quickly, let’s just run a chain for very very long - that should be fine, right?

Not really. Up until now I only showed examples where the distribution is mostly gathered together. Let’s see what happens when there are two separated islands:

If we use a small $\epsilon$ when there are islands in the distribution, then Langevin might converge to a good representation of one of the islands, but the samples won’t “hop” between the islands

Adding Metropolis-Hastings

I should mention that all the examples so far were in 2D, so we could see the distribution and the samples. In 2D, calibrating $\epsilon$ isn’t too hard - you just have to try a couple of times and you can actually see the results. However, most practical use cases are in much higher dimensionalities. In such cases, we can’t see the distribution and we only really have marginal signals of whether convergence was reached. This means that understanding whether the chain has converged or not is much, much, more difficult.

One way to make life (a bit) simpler is by making sure that, no matter what $\epsilon$ we use, the chain will always converge to the correct distribution, at some point. This can be done by using the so called Metropolis-Hastings correction. I won’t go into too many details regarding this, for that you should go to the much better blog post about Metropolis-Hastings, here. Using this correction, any step size can be used, and the chain will eventually arrive at a sample from the true distribution, although we might need to wait a long while.

At a very high level, Metropolis-Hastings is a framework which allows, at each iteration, to determine whether the current step is way off mark, given the preceding step. If the current step diverges from the distribution too much, it will be thrown away (called rejections), otherwise it should be kept. Using Metropolis-Hastings together with Langevin yields the Metropolis adjusted Langevin algorithm

Annealed Langevin

Many times, calculating either the function $f(x)$ or the derivative $\nabla f(x)$ can be a very expensive computation, time-wise. In such cases, using MALA instead of just Langevin accrues a heavy cost

Instead, these models often use a heuristic common in optimization algorithms - annealing the step size. This means that the sampling procedure begins with a relatively large step size that is gradually decreased. If the step size is decreased slowly enough, and decreased to a small enough number, then the hope is that we will benefit from both sides of the scale. The starting iterations will allow the chain to mix, while iterations towards the end will “catch” the small scale behavior of the distribution. This will also allow particles to hop between islands:

Annealed Langevin is a bit harder to justify theoretically, but in practice it works quite well. The only problem is that the burden has now shifted from finding one good value for $\epsilon$ to finding a good schedule; good values for $\epsilon_t$ in every time step $t$ . One of the common schedules is the geometric decay:

\[\begin{equation} \epsilon_t = \epsilon_0\left(\beta+t\right)^{-\gamma} \end{equation}\]with $\epsilon_0, \beta, \gamma > 0$ . There are works on the optimal values for this schedule (e.g.

Conclusion

Langevin sampling is a really popular sampling algorithm, with some intimidating names and keywords thrown around whenever it is used

Despite all the keywords, I find that the algorithm itself is much simpler than people typically think. In fact, the reason it is used to much is because it is so simple to implement and utilize. The sampling algorithm itself is pretty lousy (iteration-wise) in high dimensions. However, running it is efficient enough and simple enough to actually add it into consideration.

Not to mention, the animations generated by this algorithm are pretty nice.